Let me start by thanking everybody who has read the first few posts, and has said supportive things to me about this project. Many people have Emailed me directly, and I have fought the temptation to make private messages public by inserting them as comments... except in the case of one friend, whose lengthy and, I think, brilliant thoughts on the original set of questions deserved public life. With permission, I added them to the original post, and encourage you to go check them out posthaste.

Thanks also for the contribution and forbearance of Sue, whose remark when she saw me heading out to the reading porch tonight with a Bible, a notebook, and a can of Hamm's -- "Oooh! Hamm's and Japheth's!" -- is yet another excellent illustration of why I married her.

But, back to business. My friend Tom, the closest thing I have to a clergyman, tells me that he took a semester on Genesis in seminary, and they never got past Genesis 1. Similarly, I saw an ad earlier tonight for lectures-on-tape on the Old Testament; of 24 tapes, a whopping 7 of them are on Genesis. Nearly 1/3 the material on 1 out of 40ish books.

What I'm saying is, it's hard to get a lot of momentum going here at the beginning of the Bible. It's like when you set out on that long three-week road trip, but you still have to fight through traffic to get out of your own city. I long for the open road of books like "2 Kings" or "Esther" or "Obadiah," books about which I know literally nothing. Everything will be fresh and novel, and I'll presumably be learning new stuff instead of rethinking old stuff.

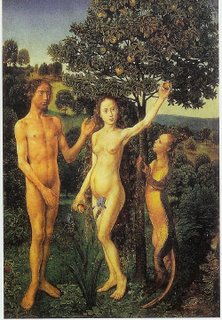

In the meantime, Genesis 3: Adam and Eve, the Snake, the Garden, the Expulsion. Not exactly a story I've never encountered before.

Genesis 3

Now, the most interesting thing about the story of Adam and Eve is that it is only a few paragraphs long. Considering its ENORMOUS place in our mythic and psychological world, you kind of expect it to be strung out over many pages, to occupy vastly more textual room than, well, whatever happens in 2 Kings. But no. It's tiny.

Moreover, it's half curse. After the key events (God sets tree off limit, snake tempts Eve, Eve eats and shares with Adam), God does some really, really serious cursing. Actually, the snake gets it first: has to crawl on belly, eat dirt, and be repulsive to humans. Then, women: pain of childbirth, and your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you" (3:16).

Time out. This curse is somewhat redundant, since Adam seemed pretty much the boss of his "helper" by the end of last week's installment. But where the end of Genesis 2 had man implicitly above woman in the pecking order, G3:16 really throws it right in your face. Hard to argue with he will rule over you. ("Your desire will be for your husband" seems like unwelcome news in the lesbian community, for that matter.) All in all, it's a difficult couple of clauses for us fans of inclusive family values.

Back to the curses. Since Adam is the boss of the humans, the curses that apply to all humanity are addressed to him. The upshot of these is that, instead of effortlessly receiving the garden's abundance, everybody is going to have to work through painful toil... by the sweat of your brow... or the earth will produce thorns and thistles. (cf: "I'm a-going to stay where you sleep all day, where they hung the jerk who invented work, in the Big Rock Candy Mountains.") With a goodbye present of a change of clothing, the first couple are sent out from the Garden to learn agriculture by doing.

Harsh! Dude! Harsh! The punishment does not, to my way of thinking, fit the crime. A single piece of purloined fruit does not, in most human schemes of justice, merit exile and complete loss of a lifestyle to which one has become accustomed for both the perpitrators and all of their descendents, in perpetuity. Indeed, this might be our first encounter with the most troubling question on the table: is God good to lay out this extravagent round of curses?

But I have a hard time taking that question seriously, for the simple reason that I have a hard time making head or tails of G3. The key point of confusion, for my money, is "what is the nature of that piece of fruit?" This is VERY murky. It's certainly not like any fruit I'm familiar with, not even starfruit.

What's in that fruit, anyway?

Clue I (3:3): Eve says that God said that she and Adam weren't to eat or even touch the fruit, or they would die. (This turns out not to be true, so Eve either lied about it, misunderstood God, or was fibbed to by God.)

Clue II (3:4-5): The snake says "No, you won't die; you'll become more like God, and know the difference between good and evil." (We are clearly not supposed to think much of the snake, but everything he says turns out to be correct.)

Clue III (3:7): The fruit is super-tasty. Once eaten, A & E know the difference between Good and Evil (3:22). This knowledge, specifically, seems to consist of awareness that they are naked, and that being naked is shameful and bad. (This seems extremely hard on sexuality, not to mention my aversion to pajamas).

Clue IV (3:22): God is afraid that if the fruit is eaten again -- or perhaps if the fruit from another tree, the "tree of life," is eaten, it's not entirely clear which -- that humans will become immortal, and live forever. This would be very bad, and is why humans are banished from the Garden. (Why this would be bad is not addressed.)

Clue V: (3:22): Having eaten the fruit, humans are, according to God, "now become like one of us, knowing good and evil."

Help me out here, folks. Is this an elaborate story about sex, cleaned up for the kids through a self-referential concern for the dirty nastiness of the subject? But if so, what are the implications for the literal truth of the Bible, not to say its coherence?

But, if the story doesn't really make a lot of sense on its own merits, it does rock the house in the imagery department. That piece of fruit is an unbeatable evocation of temptation, and the serpant out-mephistopholeses Mephistopholes. If you follow me. The fig leaves are classic. (Interestingly, the chapter ends on an image that's a bit of a clunker, almost universally forgotten: After he drove the man out, he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life.(3:24))

Genesis 3 also contains one of my favorite phrases in the Bible, when A&E hear the sound of the Lord God as he was walking in the garden in the cool of the day (3:8). If we are indeed like God, it is hopeful to me that we are like the God who enjoys a stroll in the garden, before it gets too hot.

Thanks for reading, friend. Next up: "Sibling Rivalry of the Old School," or, Raising Cain.

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Gen 3: The Fall of Man, man.

Posted by Michael5000 at 8/03/2006 09:07:00 PM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

7 comments:

To your question, "Is God a Republican?"

Thus far, he seems to be, at least in the conservative family values sense (God's views on taxing the rich are yet to be determined). Avoid temptations, do as your told, nakedness is bad... Other than the fact that I was always told you're supposed to eat fruit, these seem like some very good prescriptions for being a "good" person.

Well, in the next chapter God shows Himself a red meat sort of guy, with no regard for the sacrifice of organic farmers. . .

I have been kind of obsessing on the tree of life. If knowledge of good and evil was too godlike a gift for the humans to handle, why wasn't immortality also off limits? It wasn't forbidden to Adam and Eve until after they ate from the tree of the knowledge of g & e. If they had followed God's one rule, they could have been eternally innocent immortals with no moral conscience. And how boring would that be? Sounds like Sim Stasis, not the lab experiment I'd conduct if I were God. Or else, what if they had eaten both fruits in the opposite order, life and then knowledge? Would we have a little pantheon on our hands? Eden as Asgard or Mount Olympus? How would God have punished that misdeed?

I am reminded of a literature professor's exasperation at students' endless what if's--What if Hamlet had killed Claudius instead of dawdling?--and his response "It's a play! He doesn't exist outside the text!" And sure, duh, if we're talking about a creation myth here, we're never gonna end up with one that ends "Adam and Eve obeyed the rules, and that's why we're immortal and don't have to work for a living." Still, I expect a certain amount of internal logic in my narratives.

As for whether or not God "overreacted," No, because there was only one rule on the books. One rule, and they broke it. And Yes, because what can you reasonably expect from people when you deny them any knowledge between good and evil?

Very interesting and mad props to you for taking on such a daunting task. I apparently read the Bible when I was a kid. My guess is I turned the pages...

If you are so intrigued with Genesis, I highly recommend reading Paradise Lost--probably my favorite book I was read in Lit class, but would never have the gumption to read on my own.

Anyway, looking forward to future posts.

It's too simple to equate the fruit with carnal knowledge. The story is a cautionary tale about knowledge in the broadest sense. Every etiological story equates knowledge with grief. Period. The harshness of the Christian god and expulsion from the garden hardly equates to Prometheus bound, his inviolate liver being eaten out for all eternity by an eagle (image of Zeus), Cronos eating his children or any of the horrific dismemberments of the Egyptian creation gods. But why, as Michael notes, are our stories of knowledge "half curse?"

As an educator I have to spend some time thinking about this. I know that, staring at me with bovine torpor though they might be at any given moment, my students enter the classroom with the expectation of KNOWLEDGE. Not the enlightenment kind, perhaps, but at least something that will equate to sounding better in a job interview down the road. As I am teaching them _Beowulf_, it naturally occurs to me that the content is not going to be the thing that puts them over the edge in that interview for Sprint or shift manager at Hertz Rent-A-Car.

Should he try to impress said future employer with his newfangled and largely mangled Old English: "Wod under wolcnum, under mistleofum, Grendel gongon, goddes yrre baer!" the proud holder of the Bachelor of Arts degree will be shown the door. To security.

What I am hoping for in the content is not that the knowledge of content itself will remake the students in its own image (do we really need more heroic Geats, after all?) but some sense of play, some sense of involvement in the endeaavor for its own sake. Some engagement with the stuff of the world. Surely the Christian god in his vacuum-sealed supremacy must have wanted the same thing?

When I pull the giant, papier mache Grendel arm from beneath the lecturn housing, it's not a gasp of admiration I'm hoping for. The black fingernails are falling off, the red stuffing is coming out at the shoulder, exposing newsprint, and one finger is sadly held on by tape. But even if I were capable of special effects extraordinary like, say, parting an ocean, would the desired effect be salacious, fearful kneeling?

"Disarming!" I'm hoping one of the student will say to the papier mache limg. Or that one of them will get inspired to, say, try to bring Faulkner to life later in Intro to Lit. The point is that this knowledge has to spark some creativity in them if it's going to catch light at all. The light of the world gets pretty dim when everybody is studiously reading by it and nobody is fanning the flame (or splitting the current, if we are making this a post-Edison light metaphor.)

As a social being, the image of the angry god(s) necessarily haunt me in this enterprise of teaching. If young people have been indoctrinated by their cultural mythos into the assumption that knowledge is dangerous, what kinds of risks, creative or otherwise, can I expect them to take?

Literature gives us some good answers. Reading the Bible historically is a good approach, but we cannot really know ourselves or our history except in narrative, and so the study of literature is helpful. There's a reason the curse is almost always more than half the story. (I could invoke Freytag's triangle and the way the warning prolongs suspense during the rising action scenes, but the archetypal story is older than that.) Quite simply, the curse itself _is_ the story.

Most of Old English battles as preserved in poetry are (conspicuously like the NFL) nothing more than boasting and taunting, extended cursing occasionally interrupted by bouts of violence. It's important as well that the later, Christianized _Beowulf_ contains that line I so gratuitously peppered into the earlier paragraph: Across the dark fens, under the mist mantle, Grendel came creeping... Bearing God's Anger.

Yes, Grendel, because he's not going to win, is equated with the cursed race of Cain. Like all our enemies, this one is god-cursed. Hard enough to win in battle when someone's got you in a terrible arm hold, but the weight of God's anger has to really get in the way, I'd think.

We could look to any number of curse stories and see that the character always goes ahead with the temptation, no matter how severe the warning, no matter how great the burden. Psyche will see Cupid (the original beauty and beast story), Pandora will open the box. That's pretty much the purpose of drawing the line in the sand--to have somebody cross it. Not just to generate those exciting battle scenes, spear-thwanging and shield clashy though those are. No, we must have temptation, we must have limitation, because without it we could not have transgression, and without transgression, we could not have transformation or the birth of the world.

Somehow, through this pathetically long preface I've gotten to the gist of what I want to say here, and that is that the creation myths all begin in a world of unity. Sky and earth unified. Dark and light unified. This world, sealed upon itself. This great linty navel, this ur-state is NO PARADISE! It is not alive. Nothing is moving between two worlds because there is no between. There is only That Which Is. It is a closed system, endlessly fecundating itself.

Conspicuous image of how we're supposed to read this: Cronos lies endlessly over Rhea, but her children can never be born because he keeps eating them. All, in a world of such unity, is swallowed back into itself. The Garden of Eden is sealed upon itself. Only when it becomes a garden of eatin' do we see movement, dynamism, the stuff of life.

The world cannot be born until transgression. Here we get the son who overthrows the father (or, in the case of Zeus, the son who cuts off the father's penis with a scythe and tosses it into the ocean, giving birth to Aphrodite--apparently a rib gets you eve, but a Titan penis gets you the goddess of love.) Most of the creation myths involve the rise of the young hero who is able to act ONLY BECAUSE he knows so little. He is motivated to action by those who understand that the world cannot be born without this cleaving in twain, but the hero would not transgress if he were not unknowing. As soon as he acts, he recognizes that his actions have greater implications than he realized. For every action there will be a reaction, and an action, and so on. The world, through his first transgression, has been brought into being in its endless begetting and giving of grief.

Welcome the world! Or, as we say in Intro to Lit: "Welcome to Grief!"

The problem with the Christian myth is that it neglects this step that all other creation stories have. You got yer transgression, and your female abettin' of young Adam, but where is the throwing over of the father, the willful cleaving of the unified world into the binaries that constitute how we know and become in this world?

We cannot know except in binaries. Subvert them though we might wish to, our world is a world of comparison. Krisnamurti writes that fear is not a physiological response, the body's preparation for fight or flight. It is an internalized, psychological condition. One cannot live in the (unified, whole) moment that one inhabits, because one is always comparing to a former moment or imagining a future moment. We do not exist in the present, Krisnamurti says, because the nature of knowledge is that it elapses the present in a series of binary comparisons with the past and the future.

No wonder knowledge is equated with eternal damnation. No wonder it brings such pain. Our lives are elapsed in an absent present, feeding a past and future we can neither know nor change. But consider the alternative: a world of unified perfection, without comparison. An eternal present. How can we know and feel anything at all without comparison? Darkness and light, cold and warmth?

The art of story (which is really what I'm after whether we're learning Beowulf or Dry September or Genesis) lies in the series of (nearly Hegelian, dialectical) inversions. Love, we know, begets hate in every story. As soon as we create a category of "that which we love," by negation we necessarily imply a category of that for which we feel the opposite, that which is not love. The love of Romeo and Juliet is contraposed to the hate it begets in their passion play. And somewhere between those two polarities is a line that, despite everyone's best warnings, gets crossed. The important part of a good story (and the part that's missing from the Christian monomyth) is the next inversion. What is the opposite of hate? How do you invert that again?

If you turn it back into love, then you merely create that unified whole again, all the energy cycling back into itself like an alkaline battery. The opposite of hate at this point is to change the *nature* of hate. Rather than the outer-direted emotion, it becomes inward-directed. The character looks at what he has wrought and loaths himself. And after that, we get the part that comes with denoument... the potential for self love at last.

Amy Bloom says that love invents us. I think she's right about that, but from an archetypal, story-analysis point of view the reason I think so is that love is an emotion that sets the series of inversions and transgressions in motion. For god so loved the world... that he set it up again and again for transgression. Go ahead, the Christian god seems to be saying (if we cast him as Robert Conrad): "knock this battery off my shoulder."

And so we do. Again and again. Thou shalt not is a precursor to the necessary transgression that begins the transformation that is the beautiful trouble of this world.

There is a reason for the image of food as a transgressive element, too. It is literally a thing we take in, which changes the body. It quite nicely symbolizes knowledge, then, which we also cannot take in without it changing us. And this is about the point you hope to get to if you find yourself teaching _Beowulf_ in Intro to Lit, which is to say to young people that, uncertain though the proposition might be and fraught with the risk of absurdity and wrong answers... without the attempt to take in and be transformed by knowledge, the student has come an awful long way to remain unmoved.

Thank (god) Adam and Eve left that garden with their gnashing thoughts, their regrets, their toil and trouble. As story protagonists, they were set up, it's sure, by The Almighty, to bring us the pain by which we will know the only pleasure that is life in the world. And if you want to accuse The Big A of egotism, you might as well throw in here that we could never contemplate even in the abstract the notion of a godlike limitlessness if we did not inhabit a world of human limitation. The dramatic irony here is that we could only have appreciated what we were given and the nature of the giver by transgressing and cursing ourselves to a world of limitation. Our thanklessness gives rise to our only hope of thankfulness. Great inversion! And if the prophets had finished the story they would have written that last chapter where we get to the next inversion of thankfulness, which is gratitude not to the creator and his limitlessness, but gratitude for our failed, flawed selves. As we read their story, we ought to imagine our puny voices generations in their future, calling out to Adam and Eve, (in Amy Fleury's words), "Mother, Father... birth us into the beautiful trouble of this world."

--ASW

I'm enjoying your blog. Here are some of my thoughts about the fruit. (Numbered according to your clues.)

1. Partaking of the fruit caused "spiritual death" which is separation from God. Jesus Christ overcame physical and spiritual death through his sacrifice.

2. The fruit of knowledge causes them to leave the state of innocence. Like small children they did not understand nakedness until they "grew up." They became carnal, and as such recognized the need for clothing.

3. God does not want them to partake of the tree of life in their carnal state. If they did they would live forever as sinners. There first needs to be a Redeemer to save them and all their posterity as they are no longer innocent and can not be with him until they are clean and pure.

4. Adam and Eve could not have known good if they did not partake of the fruit and experienced the evil. It is the contrast that is so essential. Can you know light if you don't know darkness? Interesting how God says they "become like one of us." Why do you think this is plural?

I think that the most important point of the whole story is this:

God did not create robots. He could have - but what would be the point? We have a choice - always. Which is why the tree was put in the garden. Choose to obey and trust God - or choose to disobey. They chose to disobey - regardless of the "why". Sad but true - end of story.

Some things to note re: your questions about the punishment of death for eating the fruit - and the serpents role = truth or lie:

ADAM'S SIN BROUGHT DEATH

Let us consider death in God's original plan. The passages most often referred to on this topic, Romans 5:12-21 and I Corinthians 15:20-26, clearly illustrate the fact that our death resulted from Adam's sin. Yet the Bible has more to say which helps us bring this issue into focus.

The wording of Genesis 2:17 is very clear—"but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die." What did God mean by "die?" If we examine the events of the fall, we will find that Adam did not physically die when he first ate the fruit, tempting many to say that Adam fell only in a spiritual sense. But we must note two things that differentiate Adam from ourselves. First, Adam was created perfect and sinless. Second, because he was created sinless, he was not originally condemned to physical death. When Adam ate from that tree, he truly died, just as God promised he would. He died spiritually at that moment, but he was also cursed with the ultimate reality of physical death. Physical death is the result of spiritual death, so that 930 years later, Adam's body finally caught up to his spirit.

Genesis 3:5: Knowing Good and Evil

Not everything the serpent said in Genesis 3 was a lie. This is common among deceivers: they sprinkle truth with lies. One thing the serpent said to Eve was that she would be like God, knowing good and evil.

Was this a “prophecy come true” for Satan (the influencer behind the serpent)? After all, in Genesis 3:22, God reveals that man had become like God, knowing good and evil. By no means is this a fulfilled prophecy of Satan, but common knowledge to him. As Satan had sinned in heavenly realms, God then experienced (i.e., knew intimately) a distinction between good and evil (evil is basically the absence of good).

When Adam and Eve sinned, they (and we) were subject to the same thing: an experiential knowledge of distinction between good and evil. So, in that sense, they had become like God. This is to be distinguished from being or becoming God.

Post a Comment