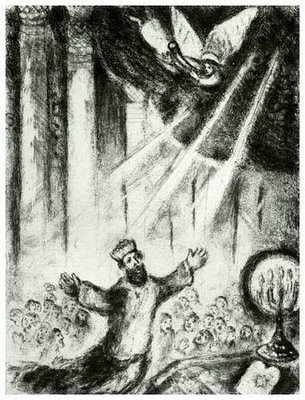

Manasseh

In 2 Kings 21:1-18, we learn that Manasseh about as bad as it gets in terms of religious orthodoxy. It doesn't look like there is any diety that he didn't worship, and he builds altars to just about anybody with a cult right inside the Temple. Manasseh leads the people of Judah so far astray, we are told, that they become worse than the peoples that God had wiped out to make space for the Israelites.

We are given the same story in 2 Chronicles 33:1-20, but the story continues on in an interesting arc. In the Chronicles account, God punishes the lapsed Israelites by having them defeated by the Assyrians, and Manasseh is led on an unpleasant trip to Babylon in shackles and with a hook in his nose. Perhaps not surprisingly, this experience makes him feel pretty repentent, and in his distress he sought the favor of the Lord his God and humbled himself greatly before the God of his fathers. God is sympathetic, and somehow he brought him back to Jerusalem and to his kingdom. A reformed Manasseh becomes a more effective king, and has all the altars he had built early in his reign torn down again.

Amon

A young man who serves only two years before he is assassinated, Amon gets the last four verses of 2 Kings 21 and the last six of 2 Chronicles 33.

Josiah

Josiah is the king of Judah during whose reign Moses' Book of the Law is found in the Temple. The account in Chronicles 34-35 is pretty much the same as that in 2 Kings 22-23. Realizing that the Israelites have strayed far from the Law of Moses, Josiah does his best to restore religious practice.

In the Kings version, God appreciates Josiah's efforts but subsequently allows Judah to be destroyed anyway because he's still so angry about Manasseh. This doesn't work in Chronicles, where Manasseh has managed to rehabilitate himself. In this version, God informs Josiah -- through a female prophet named Huldah -- that he will destroy Judah out of a more general anger for the generations of religious neglect. Since God promises not to start until Josiah is dead, the people must be especially horrified to see him attack, for no good reason I can divine, an Egyptian army on its way to war with someone else. He is killed by archers, and it's all over but the shouting for the last independant Israelite kingdom.

The Shouting

Johoahaz, Johoiakim, Johoiachin, and Zedekiah are covered in 2 Kings 23:31 - 24:7 and 2 Chronicles 36:1-14. None of them is able to do anything but preside over the erosion of Judah by the rising powers of Egypt and Assyria. Both books end with an account of the fall of Jerusalem, the corruption and destruction of the population of Judah, and the enslavement of everyone who remained in Babylon.

Both books, however, end on a positive note. 2 Kings ended with the release of Jehoiachin, the penultimate king of Judah, and his humane treatment under King Evil-Merodach of Assyria. Here in 2 Chronicles, if I'm reading it right, an Assyrian king apparently undergoes a religious conversion after the Israelites have been in exile for seventy years. Here's how it ends:

22 In the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, in order to fulfill the word of the LORD spoken by Jeremiah, the LORD moved the heart of Cyrus king of Persia to make a proclamation throughout his realm and to put it in writing:Well, THAT certainly seems like a lucky break for the Israelites. Perhaps we'll read all about it next time.

23 "This is what Cyrus king of Persia says: " 'The LORD, the God of heaven, has

given me all the kingdoms of the earth and he has appointed me to build a temple for him at Jerusalem in Judah. Anyone of his people among you—may the LORD his God be with him, and let him go up.' "

But first!

It's time for the annual MRtB Winter Sabbatical. In fact, it's a little past time, but I wanted to finish up Chronicles before taking the break. I'll start up again sometime in January with the Book of Ezra. It's kind of exciting to me that I'm getting into some of those really short chapters of the Old Testament that I've always wondered about. What's in those chapters, anyway? Guess we'll find out!

Got Stats?

I've finished 14 of the Bible's 66 books now, which puts me 21.2% of the way in. In chapters, though, I've finished 403 of 1189, a little more than a third of the way through (33.9%). My favorite measure is verses, though; having completed a whopping 12017 verses, I'm 38.6% of the way through the 31102 verse Bible.

I stayed on task pretty well in 2008, covering 7124 verses (compared to 4687 in 2007 and 206 in 2006). At the current pace, I would wrap up in Summer 2011, at which point I guess I'll have to find a new hobby.

Thanks to anybody who's reading. See ya sometime in January!